Charge Kimberly Murray for Hate Crimes, Not Me

Facts, not Indigenous activist mantras should underlie rule of law and Freedom of Speech

By Michelle Stirling ©2024

I am glad that Christine van Geyn of the Canadian Constitution Foundation is trying to keep me from going to jail for being an Indian Residential School factualist, but I dispute her claims in her recent Globe and Mail op-ed on this matter.

She wrote:

To be clear, it is foolishness to try to minimize the harm many Indigenous children and families suffered at and because of residential schools.

Many children and families benefitted. Can we not talk about that? Robert Carney was an eminent Canadian historian who was very critical of the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples, the forerunner to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission. He is father of the much more famous Mark Carney, former governor of the Banks of Canada and England. Carney explained that residential schools “in some cases well into the twentieth century, took in sick, dying, abandoned, orphaned, physically and mentally handicapped children, from newborns to late adolescents, as well as adults who asked for refuge and other forms of assistance.”

That some children were harmed is well-documented and ample compensation in the billions of dollars has been paid to those who claimed the lump sum Common Experience payment of $10,000 for the first year and $3,000 for every year after. Common Experience payments were made to all former students who applied whether the individual claimed harm or not. Other former students applied for the Individual Assessment Process (IAP). This allowed an individual to explain the details of the harms done to them, to a small, protected review board, and based on their claims, payouts could be upwards of $200,000. Persons accused of causing the harm were offered $2,000 to fight to clear their name in court – a paltry sum.

The “high” standard of IAP proof of abuse was thus:

“The standard track is used for dealing with claims of abuse. Most IAP claims are dealt with in this track. Claims under the standard track are less complex because claimants must prove their claims solely on a balance of probabilities. That means the adjudicator makes a decision based on whether it is more likely than not that the abuse happened.”

“For most residential school abuse claims, the only evidence of what happened is the testimony of the claimant. There are rarely any witnesses or other evidence available to help claimants prove their abuse claims.”

That many children benefitted from their Indian Residential School experience is a story less told; a story censored.

Indeed, in the process of gathering recollections for the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, the person charged with interviewing former staff and administrators, who would have provided the adult perspective of school operations, was told her budget was cut from $100,000 to $10,000, and that none of her recorded interviews would be transcribed.

Recall that Canadian taxpayers shelled out $72 million dollars for the Truth and Reconciliation Commission. It is not like there was no budget.

So. The full truth was censored for the production of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission Reports. The true story was minimized. Perhaps the people who did that should be charged with residential school denialism.

The TRC heard from ~6,500 former students. This seems like a very large number, but it is only 4% of all the people who had attended. Most of these students attended in the latter years of the schools operations, all of which were closed by 1997; many of the schools in the last 20-30 years were run by Indigenous First Nations groups.

Thus, it seems people are claiming that Indigenous people caused these allegedly genocidal harms to their own people, but Canadian taxpayers had to pay the compensation for it. Should those First Nations bands be charged with genocide?

Ms. Van Geyn continues:

“We know that there were children who were forced to attend, and there is no justification for forcibly separating a child from their loving family.”

Where are the records, aside from recollections, of forcible separation?

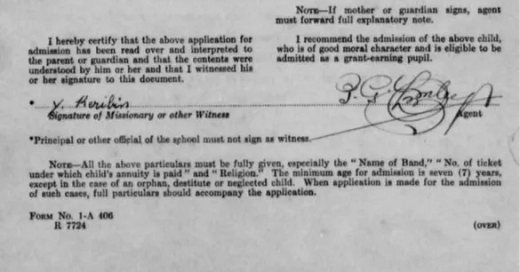

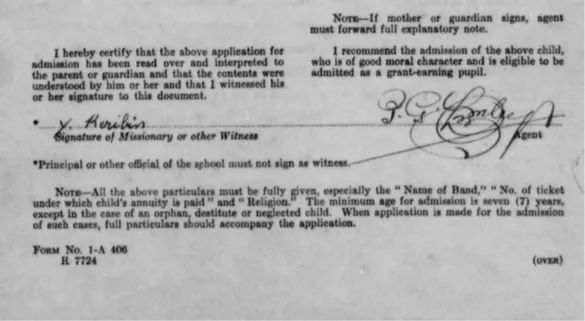

As the admission form shows, children could be admitted below the age of enrollment if the child was orphaned, if the family was destitute or if there was child neglect.

There is ample justification for separation if it means saving the child from destitution or neglect, then, as now. It may be that the child remembers the situation as one of a forcible separation, but do we have actual documentation proving that it was ‘forcible separation from a loving family?’

Likewise, in very large families like that of Wilton Littlechild (11 siblings), Doris Young (15 siblings living in a small house meant for five people), Phil Fontaine (10 siblings), the care and feeding of so many children could be overwhelming for parents relying on just hunting and trapping. The three Osbourne sisters from Kimberly Murray’s “Sacred Responsibilities” report were enrolled by their parents in the Depression years, hoping for better care and sustenance. All three girls ultimately died of TB, two of them as young adults (Isobel at age 22, and Nora at age 25). It is not clear why Kimberly Murray included them in her report as Indian Residential School deaths.

There are instances where a marriage broke up or one spouse died, or upon marriage, children from other lovers might be abandoned to a residential school. This happened to Debbie Paul, the woman who said she was kidnapped by a nun. When her mother - after having had four children out of wedlock - finally married, her new husband did not want her four children, so she sent two of them to the Shubenacadie Indian Residential School, and the other two to live with a relative and another family.

Paul said her mother had four children before she married. When she did marry, the step-father promptly announced that “he didn’t want her bastards.”

Paul and her younger sister went to the residential school, an older sister was sent to live with relatives in Eskasoni and another sister went to live with a family in Indian Brook.

Abandoning inconvenient children to care in an Indian Residential School was a common occurrence.

Paul was the last student to leave Shubenacadie Indian Residential School – perhaps because there was no one to go home to. Her claim of being kidnapped by a nun might rather be interpreted as a nun desperately trying to find a home for a girl with no one to go home to.

Likewise, a widower would find it impossible to care for small children and work. In one instance that I know of at the St. Joseph’s Residential School, the children remained at the school all summer so the father could work as a ranch hand.

The question is, would the children have understood their parents’ needs for childcare – effectively the equivalent of a 24/7 daycare – or have the children interpreted this as ‘forced separation’ without knowing there were enrollment documents signed by their parents?

I have watched an interview where a former Indian Residential School student denounced the fact that she was taken away to school, despite the fact that she wanted to stay with her grandfather. It was alarming that she did not reveal she was an orphan, until much later in the interview, an alarming lack of situational awareness. Both of her parents had died, she said, as had her grandmother, leaving the grandfather to try and care for this girl and her three siblings, plus nine others, as she told it. My point is that children do not understand what their parents or caregivers are up against in life. They only understand that they do not want to be abandoned or separated from familiar things or people they love.

Likewise, children who were orphaned were also dealing with that grief and loss which may be the source of memories of bloody deaths, graves and burials. TB, in particular, could be a nasty, bloody end, if someone suffered a lung hemorrhage. How horrifying for a child.

In the forgotten plague of Tuberculosis (TB), police had authority, under the health act, to forcibly remove people from a risk situation; just as they had during COVID. When TB was killing one Canadian every hour of the day, and two every hour of the night, there would be ample justification for trying to save a little one or a few siblings if the family was all infected or disabled by their condition.

In historical terms, tuberculosis was the greatest killer ever known to mankind. Accounts of TB were found in the writings of ancient Egyptians and in those of Hippocrates, and it was called “The Captain of All These Men of Death” by English writer John Bunyan. At its peak in the U.S., it killed one in every four people.

Ms. Van Geyn then says:

We know there were children who were abused, who died, and who disappeared.

Who are the children who disappeared? People keep telling us this happened, and Kimberly Murray has come up with a new term of “enforced disappearance” but no one has offered a list of names of these disappeared.

Some people, like Eric Large of the Blue Quills First Nation, have claimed on camera that every family had four or five members disappear at Indian Residential Schools. Obviously, this is a mathematical impossibility; if it were true, there would be no one left in the Blue Quills Band.

Marie Wilson, a commissioner of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, said thousands of children who died in residential schools are buried across Canada, “many of them in unmarked graves, many of them in graveyards where their own family members perhaps never had the chance to do proper spiritual farewells or sending-home ceremonies.” – Western Catholic Reporter, April 22, 2013

Marie Wilson seems to be applying a colonialist lens to Indigenous people, seeing them as pagans. Has she never heard of the annual Indigenous pilgrimage to Lac Ste. Anne in Alberta – in the rich Catholic tradition of Lourdes? Most of the families who enrolled their children in Indian Residential Schools had adopted Christianity (whether Roman Catholicism or other) decades or generations before. Thus, just as Catholic parents today prefer to send their children to a Catholic school, so it was in years past. In most cases, when one of the 423 children known to have died while at one of the 139 Indian Residential Schools, over the course of 113 years, the child’s body was sent home for burial on reserve. Most of those burials were with full Christian burial rites as the parents would have chosen. But if not, on reserve any parent could have chosen to have “proper spiritual farewells or sending-home ceremonies.”

If the child died of a contagious condition that precluded transport, or if the parents were out on the trap line and could not be reached in a timely way, the child would have been buried at the mission graveyard, or in a handful of instances, the consecrated ground at a remotely located school. Remember, in these isolated locations, the community had to be self-sufficient and to address both the dignity of the deceased with Christian rites, and public health and sanitation with a proper burial. As Indigenous priest, Father Christino Bouvette has pointed out, “…wherever people live you’re going to have a cemetery, because wherever people live, people die.”

Life and death are part and parcel of our existence. Having a graveyard at a residential school, especially one in an isolated location, would be essential, not macabre as constantly promoted by NDP MP Leah Gazan, author of Bill C-413, who says “no school should have grave sites around it.”

But you may protest, what of the 3,000+ children the TRC claimed died. This number included children who were enrolled at a school, but died elsewhere, or children who had died within a year of leaving the school, no matter the cause of death. It should matter to you, the taxpayer, or to people like me – who might face jail for writing this – that a child who died of a car accident within a year of attending, unrelated to transportation to or from an Indian Residential School or school activity, is counted as part of the TRC calculations of the numbers of children who died ‘at’ residential school.

Claims that babies or children were incinerated as in the shock-u-mentary “Sugarcane” are ludicrous as Christianity, particularly Roman Catholicism, reveres the ‘mortal coil’ and believes in the ultimate Resurrection; thus, treating the dead with dignity was and is a very high priority. Not to mention, no school garbage burner could reach the high intensity heat required for cremation. To not have done due diligence on this matter shows the Kimberly Murray report to have an embarrassing lack of credibility.

Another point to help keep me out of jail, let Ms. Van Geyn know for the record that there were no ‘stuff of horror films’ at Indian Residential Schools. Kimberly Murray’s reports all suffer from an extreme case of presentism and no historical context.

Ms. Murray’s report references some of the horrifying stories of medical experimentation on children, including the use of experimental vaccines, and of pharmaceutical and nutritional testing. This is the stuff of horror films.

Ms. Van Geyn is lacking context. Lacking historical perspective. This is from “Medical Survey of Nutrition Among the Northern Manitoba Indians” by Moore et al (1946) CMAJ

Formerly the Indians lived in wigwams and still do in some areas. Today the Indian is copying the white man and lives during the winter months in small one-roomed shacks (Fig. 1). Frequently the conditions are almost unbelievable; as many as 10 to 12 people living in a shack 12 feet square. The only furniture may consist of a stove in the centre and a small table or stool (Fig. 2). Sometimes there may be one broken-down single bed, but the majority sleep on the floor. The door is seldom more than 5 feet high and is covered by a blanket or old piece of canvas to keep out the wind. Two small windows let in the light, and the sole source of ventilation is the stove and the fairly large hole in the flat roof for the stove-pipe. Their sanitary habits are very primitive. Refuse and excreta litter the snow in the immediate vicinity of the house. With the advent of spring the whole family moves to tents, which they set up a few hundred feet away, and trust to the spring -and summer rains to wash away the refuse. During the summer months they frequently change the location of the tents as they move about in their quest for food.

As Dr. George Wherrett’s book “The Miracle of the Empty Beds” shows, the TB vaccine had already been tested and the need to find a cure for TB was urgent, particularly for children at Indian Residential Schools. Many were there because their own parents had died of TB, and they were left infected.

It is likely that through campfire story telling over the years, some of the painful treatments that people endured for TB as children or adults became conflated with memories of people’s time at Indian Residential Schools. Some students went from school to sanatorium and back. TB can also make people hallucinate. There is little mention of the scope of the TB crisis in Canada at the time nor any reference that this illness may have affected perceptions.

Ultimately, we do know that we do NOT have an accurate record of what went on at Indian Residential Schools from the TRC because the people who came to give their recollections were children at the time these events occurred. Though eye witness statements are very convincing, in terms of jurisprudence and psychology, eye-witness statements and Historical Sexual Assault claims are not considered to be reliable. Yet Canadians have paid out billions in compensation with few questions asked.

The most accurate records are those of the Department of Indian Affairs, the school records, the diaries of the Oblate fathers and Grey nuns, that were recorded at the time, and in papers by historians like Robert Carney that predate the mass graves psychosis, and various books by people like Dr. Hugh Dempsey, my mentor in historical research.

So, is Kimberly Murray planning on making it a criminal offense for me to point that out?

Many people have misunderstood what the Truth and Reconciliation Commission documents are. They are a collection of statements from people who spoke in an open ‘witnessing’ context. There was no cross examination and no requirement to prove the validity in any way, of anything that was said.

“Groupthink” tends to take over in such a context; likewise, people are humbled by the “social proof” of the herd mentality. And furthermore, when people entered the room, they were met by this sign which certainly set a biased tone from the get-go.

The kiosk above greeted people who were coming to speak at TRC events. The statements on it are incorrect. At its peak, enrollment in the IRS was one third of status Indian children. In most periods of IRS operations, particularly after the 1950s, the proportion of attendance was far lower. In TRC History Part 1, it states that in 1968 only 13 percent of First Nation kids were enrolled in residential schools, and that that statistic does not reflect the fact that many status kids were not enrolled in any school at all. By that time, the majority of the so-called "residential school" students were boarding in former residential schools while by day they attended nearby public schools. They were boarding, simply because their communities were too far away for daily bussing to the public schools.

It is unlikely that parents were left in communities devoid of children, particularly when families were very large back then – 10 -15 children.

Let me close by saying to Ms. Van Geyn and to Kimberly Murray, the following:

“Not having the names of the children who are suspected to have died in the residential schools, we can’t focus our search to identify these particular files quickly.”

• Dr. John K. Younes, Chief Medical Examiner, Province of Manitoba

The above quote comes from the Senate report “Missing Records, Missing Children.” This is the crux of the whole matter.

This is a phantom genocide of children with no names and over one hundred years of history with no missing persons reports filed by parents. This is a case of mass psychosis on a national scale.

Litigation directors of organizations must not accept the Indigenous activist mantras such as “we know people disappeared” without proof. Ms. Van Geyn’s organization is meant to protect the constitutional rights of people like me, who may be charged with a hate crime for writing down these facts, thus, I hope that there will be a full examination of the facts first, and not just a repetition of activist mantras.

I would go as far as to say that Kimberly Murray’s work and her demands to criminalize residential school factualism is a hate crime toward me. If anything, she should be charged.

Please review my recent discussion with criminal defence lawyer, Nicholas Wansbutter on “Don’t Talk TV.”

Van Geyn is an example of the otherwise good writers who deem it necessary to virtue signal about things they obviously know little about before making their main point. Children at residential schools didn’t “disappear” etc. The fact is that negative aspects of residential schools have been vastly overblown, while positive aspects have been ignored completely. Many children had bad experiences there, but most of the Indian leaders of the past generations were educated there. It was a mixed bag. Great article!

Michelle Stirling, one of Canada's truly great journalists, writes that "a former Indian Residential School student denounced the fact that she was taken away to school, despite the fact that she wanted to stay with her grandfather. It was alarming that she did not reveal she was an orphan.... Both of her parents had died, she said, as had her grandmother, leaving the grandfather to try and care for this girl and her three siblings, plus nine others, as she told it. My point is that children do not understand what their parents or caregivers are up against in life." The girl had many reasons to feel trauma in her young life but the point of residential schools was to give her an education and an escape from destitution.