The Bitter Roots of "Sugarcane"

How a Shock-u-mentary Blood Libels the Catholic Church and Canadian History

I made a mini-documentary to rebut the blood libel against Canada in the National Geographic film “Sugarcane.”

Watch my documentary here:

https://rumble.com/v5i558i-the-bitter-roots-of-sugarcane.html

Or on VIMEO:

<div style="padding:56.25% 0 0 0;position:relative;"><iframe src="

" frameborder="0" allow="autoplay; fullscreen; picture-in-picture; clipboard-write" style="position:absolute;top:0;left:0;width:100%;height:100%;" title="The Bitter Roots of "Sugarcane""></iframe></div><script src="https://player.vimeo.com/api/player.js"></script>

If you haven’t seen the documentary, I discuss it in detail below. This post was originally on Medium.

Deeply Deceptive Documentary “Sugarcane”

National Geographic Needed a Factcheck — Here it is.

By Michelle Stirling ©2024 with additional research by Nina Green

“Sugarcane” reviews are all over the press, all positive, and all are super spreaders of more deceptions about Indian Residential School history in Canada. National Geographic picked up this documentary for distribution after its win at the Sundance Film Festival. Carolyn Bernstein, Executive Vice President of National Geographic Documentary Films said at the time: “National Geographic Documentary Films has a long track record of championing epic and important stories that awaken audiences and transcend their moment.”

According to a report in “Deadline” of Feb. 21, 2024, “Deadline understands that the Disney-owned factual brand has struck a deal in the low seven-figures.”

Let’s awaken National Geographic’s factual brand and its audiences with some behind-the-scenes facts.

Trashcan Baby

The film purports to tell the story of Indigenous artist Ed Archie NoiseCat, who was found by accident by the school’s dairyman, as an abandoned newborn in the incinerator at Cariboo Indian Residential School, usually referred to as St Joseph’s Indian Residential School. St. Joseph’s Catholic Mission on site predated the school.

The documentary’s premise is that the Williams Lake community on the Sugarcane Reserve secretly knew, for decades, that Catholic priests at St. Joseph’s impregnated their female students and then disposed of unwanted babies in the school incinerator.

Ed Archie NoiseCat is said to be the only infant to have survived the incinerator.

That’s one of the last titles on screen in the documentary.

The film purports to prove this case and most reviewers have bought the story hook, line and sinker.

Thus, the audience is led to believe that Ed was fathered by a priest.

The film opens with some titles of white on black with repeated twisted tropes about Indian Residential Schools which are easily debunked by historical records. It then moves into scenes of beautiful cinematography and excellent editing that lull the viewer with their elegant grace. I give the cinematography, direction and editing an A+. It is a beautiful and deeply touching film.

Just, not quite the truth.

The notion is that Julian is about to discover his father’s roots. But both men knew them years ago.

Happy Trauma Birthday, Dad.

Ed’s son and filmmaker Julian Brave Noisecat (co-director and on-screen participant) calls to wish his father “Happy Birthday” — a cruel twist that only sinks in after you watch the whole film, and one that is crueler and more exploitative when you know the facts that I’m about to tell you.

Ed is working in his artisan’s shop when he gets the call. He is meticulously carving large, beautiful Indigenous spirit masks. Ed asks where Julian is calling from. Julian tells him he is at the old St. Joseph’s Mission.

Cruel.

Julian and Ed have an estranged relationship that is tangled with abandonment and alcohol. But Julian is determined to ferret out the story of the past from his father and put it all on film.

His father is obviously reluctant, at one point saying about his life story, “It just goes on damaging.”

Julian thinks his father was born on the second story of St. Joseph’s Mission.

By saying this in the opening parts of the film, it therefore follows, for the viewer, that Ed was likely the product of an unknown priest impregnating Julian’s grandmother while she was a student at St. Joseph’s.

That’s the film’s thesis. That’s what the audience thinks we are going to discover.

Ed is the proof of a baby that survived these crazed priests, right?

Father was Known and Married to the Mother.

From the get-go, based on previously published material by Julian Brave NoiseCat and in bios about his father Ed, it is clear that both men know that Ed’s father was Ray Peters.

Ray Peters married Ed’s mother in 1958, according to his obituary, and they had eight children together. Ray Peters was not a Caucasian priest but an Indigenous man from Skatin, BC. Ray not only had eight children with Ed’s mother, but in total he had 17 children with 5 different women. Ray was 11 years older than Ed’s mother.

Ed was found as an abandoned newborn in the St. Joseph Indian Residential School’s incinerator on August 16, 1959. According to the Williams Lake Tribune headline news of that day that is partially read out in the film, the dairyman was coming by with his morning run and heard a strange noise coming from the incinerator. Thinking a cat had gotten trapped in there, he opened it up and found Baby Ed in an ice cream box. He saved his life.

Ed’s mother was not a student at St. Joseph’s as she was 20 years old.

The exploitation of this family tragedy by the filmmakers and National Geographic gets worse.

After the rescue of the baby, Ed’s mother was tracked down by the authorities and she was sent to jail for a year for abandoning her baby.

Thus, Baby Ed was raised for much of his early life by his paternal grandmother, a woman who died of alcohol poisoning when he was about eight, according to her death certificate.

None of these facts are in the film, though Julian or his father Ed do mention that the paternal grandmother died of hypothermia when she went outside to find her husband who had been drinking. At one point in conversation with Martina Pierre, an aunt, she asks, “Where does my brother fit in with you?” and Ed answers “He was my dad.” He adds, “There was some turmoil at the beginning.”

However, this information slips by, almost unnoticed. Ed has taken the family name of his paternal grandmother, Alice Noisecat, who married Jacob Archie. It is difficult for viewers to make family connections from the short, often emotionally charged vignettes.

“Deadline” frames the movie thus: “Sugarcane explores the lasting intergenerational legacy of trauma from the residential school system including forced family separation, physical and sexual abuse, and the destruction of Native culture and language.”

In fact, underlying this exploitative film about family dysfunction is a steady stream of alcohol.

Activist Aunty Leads the Charge

Charlene Belleau is introduced onscreen as a local Indigenous investigator of the historical claims of ‘priests and incinerator babies.’ She is Julian’s aunt and at one point performs a smudging ceremony with him in the loft of the old barn at St. Joseph’s Mission, entrusting him to be a witness to the truth of what happened. Julian appears somewhat younger in this scene, suggesting the film was pieced together over time.

Working with her is Whitney Spearing who is a Simon Fraser archeology studies graduate and “employed as an Archaeologist and Natural Resource Coordinator for the Williams Lake Indian Band.”

Charlene previously lived in Alkali Lake, British Columbia, an Indigenous village of 486 people, all of whom were entirely engulfed in alcoholism, to the point it made headline news in the LA Times in 1989. The news was that the town had recovered. One resident is quoted as saying “Because of the drinking, there was a lot of child neglect, wife abuse, rape, gang rape — the worst kind of things you can imagine.”

Something not mentioned in that 1989 article is Indian Residential Schools as the cause of anything. What changed between then and now?

Charlene was married to an RCMP officer, which may help explain how she and Whitney were able to gain access to confidential RCMP case files that no other citizen in Canada could have access to.

Charlene claims, in the film, that her uncle committed suicide at St. Joseph’s Mission, trying to escape the abuse there, and that there wasn’t even a coroner’s inquest.

“Just another dead Indian,” she says.

The historical evidence shows that her claims are false as detailed in Nina Green’s meticulous historical research.

The Augustine Allen case received media attention when a former Chief of the Alkali Lake Band and BC government appointee, Charlene Belleau, claimed that a St. Joseph’s student who died while at school, Augustine Allen, was her great-grandfather. This is clearly impossible as Augustine Allen died at 9 years of age and left no descendants.

Crime Wall

Charlene and Whitney conduct what appear to be some form of investigations with community members. One woman, Rosalin Sam, says she was sexually assaulted by a priest, and no one would believe her. She says that she went from talking about it to her mom, to the Sisters, to the principal, to the RCMP and finally that’s when her dad found out and he beat her so hard she went and bought a bottle of wine and became an alcoholic from that day.

This story is unverified but may well be true. Dozens of female victims of rape or sexual assault were ignored up until about the 1970’s as the women’s liberation movement took off.

But the problem is that there is no substantiating evidence for such claims. Rosalin Sam passed away in April of 2022, just as Ed Archie NoiseCat was about to launch an ‘awakening’ ceremony of a large 20-foot cedar totem carving of his.

Based on various interviews and timelines, names of priests, and a file at the RCMP titled “O’Conner Adoptions,” Charlene and Whitney create a crime wall with a timeline, names of priests and photos of priests, sticky notes with “Baby X,” and strings linking suspected perpetrators.

It’s very impressive, but unsubstantiated, except in a handful of cases that are already known. According to Wikipedia: “ In 1996, he [Father Hubert O’Connor] was charged with committing rape and indecent assault on two young aboriginal women during his time as principal in the 1960s." The truth is that O'Connor broke his vows in the 1960s and he did have an affair with Phyllis Bob, and she gave birth to a child, for whom O’Connor arranged an adoption. [The baby story is true except that Phyllis Bob was 22 years old, not a student, but an employee seamstress at the school; the other charges against O’Connor were stayed and ultimately all parties participated in an aboriginal healing circle which was to end things.]

According to the National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation, the St. Joseph’s school opened in 1891 and closed in 1981, a period of 90 years.

Charlene seems upset that they find in the files a connection between the school and a Vancouver charity for unwed mothers, another Catholic charity. She says of the priest, “He even knew how much it would cost…” to send a pregnant girl there.

If anyone has ever read the Bible, it is full of the stories of human beings — their love, hate, lust, greed, rage — and the miracle of birth that stems from virtually all these human emotions. A baby is a miracle. But prior to the 1970s with expanded social services and women’s liberation, single mothers were rare. Life was very difficult for a young unwed mother, especially one of school age, beset by both the restrictions of social mores of the time and the practical issues of socio-economics in a time when work options were limited for females.

The fact that St. Joseph’s Indian Residential School priests who had taken a personal vow of celibacy, had made arrangements with a Catholic charity for unwed mothers, to help girls in such a situation, does not mean that the babies were fathered by priests, but that is the clear suggestion of the film. Young men and women fall in love, engage in sex in the heat of passion, or may endure a violent rape; this was a time before contraceptives (except of the least effective kind) and before abortion (not that a Catholic facility would approve, but this was not a viable option for most young women anywhere).

But Charlene and Whitney seem determined to prove the thesis of the film.

That’s why the story of the Trashcan Baby — Ed Archie NoiseCat — is such a crucial element, and why falsely exploiting the facts as is done in “Sugarcane” is such a no-no in documentary filmmaking.

Indeed, the Merriam Webster Dictionary describes a documentary as “a presentation (such as a film or novel) expressing or dealing with factual events.”

The Irish in You

Another kind of proof offered is the story of Rick Gilbert, former Chief of the Williams Lake band.

Somehow, the filmmakers get to document Rick and his wife as they examine the on-screen results of a DNA test of Rick Gilbert which shows he is about 45% Indigenous/native, and the rest is of his genetic heritage is Irish and Scottish. As with such DNA ancestry sites, up pops a potential cousin — a McGrath. It’s not even clear if this individual is a Canadian. According to his obituary, Rick’s mother was born in 1928. So when Rick was born in 1946, she was 18, and wouldn’t have been a student at St Joseph’s because the mandatory leaving age was 16.

The image of the DNA screen flips to an archival photo of a group of children at St. Joseph’s with a Father McGrath.

Ah ha! Our documentary filmmakers have proven that Rick Gilbert is the son of a priest because there was a priest of the same name at St. Joseph’s school!

Rick’s mother also went to St. Joseph’s Indian Residential School. But was it at the same time as Father McGrath? And is Father McGrath the ONLY possible father in the region? The fact is that dozens of McGraths settled in British Columbia.

And if the thesis of the movie of ‘priests and nuns murdering illegitimate babies in the school incinerator at night’ is to be proven correct, why didn’t Rick Gilbert end up in the incinerator?

Looking at the demographics of Williams Lake, there is a very high percent of Irish, Scottish and English ethnicity. So, Rick Gilbert’s father could have been any local young man — logger, miner, rodeo king, railroad navvy, farmer, rancher, shopkeeper. Williams Lake was a cross point for everything from the gold rush to the railway.

Unless Rick Gilbert knew something more than he revealed in the film, there is no reason to assume, based on the evidence presented, that his father was a priest. Gilbert passed away in September of 2023, so we can’t ask him. His obit says he was mostly raised by his grandmother, a common theme in Indigenous families, when the nuclear family is torn apart by domestic violence and addictions.

The Burial in the Field

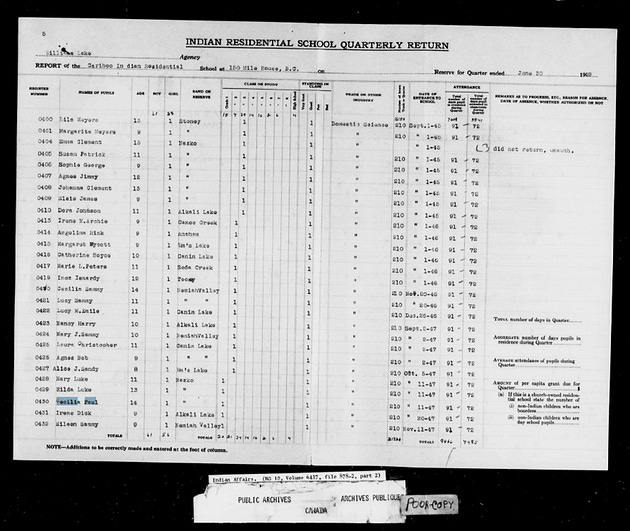

In the latter part of the film, Cecilia Paul is brought to a field near the buildings of St. Joseph’s Mission. Cecilia is listed as student number 430 and a member of the Nazko Band in the Williams Lake Agency — Cariboo Residential School pdf of microfiche files covering 1949–1952 from the Library and Public Archives of Canada.

Cecilia is wheelchair-bound and appears to have some form of cerebral palsy or other condition affecting her speech and muscle control. Her wheelchair is pushed across the field with difficulty. She is escorted by a group of about six people, an RCMP officer, and Whitney Spearing appears across the field in her safety vest with a field marker, attempting to stand where Cecilia points with her less-than-steady hand. Her colleagues ask, “Where did they bury the boy?” Cecilia explains that when she was a student there, she had gone for a walk and had gotten the strap for accidentally witnessing, what viewers assume was an illicit burial of a boy (based on the comments) and explains that this is why she can’t walk. “I was a little girl.”

Whitney now has a Ground Penetrating Radar (GPR) location to test. The RCMP officer kneels to thank Cecilia for her courage.

However, what boy was buried, what name? We do not know.

That is the persistent problem with the claim of missing children and unmarked graves.

No names.

How can you claim someone is missing if no one has a name for them? If there are no missing persons files?

Whitney and Charlene have addressed this problem on their crime board by culling the files of infant deaths in the community, calling them “Baby X” and then ascribing them by string and map pin to a priest of that era. But this is speculation, not evidence.

Are We Stupid?

Is it Charlene who says of their research and discoveries, “Did they think we’d be stupid all these years?”

Canadians are now asking themselves the same question. Did they think we’d be stupid all these years — as various payouts to First Nations and Indigenous people (of which there are 1.8 million in Canada) now reach the staggering numbers of $76 billion. Certainly, the Indigenous lawyer industry celebrates every day. Macleans magazine offers this 2006 example of the Tony Merchant firm, one of the Indian Residential School’s winners in the demands for compensation and reparations.

It is worth Canadians considering a comment of 01 August 1920, when the local Indian Agent, Achilles Thomas Wilson O’Neill Daunt (d. 1950), wrote to Ottawa advising that a rumour was being spread by an Indian in Canoe Creek named Sam about the circumstances of Augustine Allen’s death (see LAC c-8762, pp. 1127–8):

“…as a general thing when they [local native people] complain about Schools or similar Institutions, as they let their imaginations run riot, if they think that by so doing it will help them to gain what they happen to want at the moment.”

So far, the Indigenous communities have been successful to the tune of $76 billion of Canadian taxpayers money.

Trudeau said Church Burnings are Understandable

Canada has seen over 100 Catholic and other Christian churches and religious facilities burned or vandalized since the unverified proclamation of mass graves of children ‘as young as three’ by the Kamloops First Nation in 2021. At the time, Prime Minister Trudeau said, on July 2, 2021: “I understand the anger that’s out there against the federal government, against institutions like the Catholic Church. It is real and it’s fully understandable, given the shameful history that we are all becoming more and more aware of and engaging ourselves to do better as Canadians.”

However, in the documentary when Trudeau visits the Williams Lake First Nation (which coincides with former chief Rick Gilbert visiting the Vatican), the film reports that Trudeau only said: “It is unacceptable and wrong that acts of vandalism and arson are being seen across the country, including against Catholic churches.”

In the documentary, Trudeau calls Chief Willie Sellars a friend. One wonders if his friend is trying to repair the Prime Minister’s reputation by excluding what he actually said, which likely inspired more than a few church burnings.

Indeed, in the film, the only people who seem to care about Catholicism are former chief Gilbert and his chatty wife, Anna. We see them restoring books and religious artifacts to the local historic church, having taken them home out of fear that someone would burn their beloved church down.

Rick reflects on the fact that so many of the elders of the community held on to Catholicism with deep faith, and he concludes that there must be some profound truth to it for them to have held it in such esteem. This is the only evidence of piety or love for Catholicism that we see in the film which otherwise makes every effort to denigrate and destroy the reputations of priests and nuns, providing historical tidbits with no historical context.

In a scene in the fenced community graveyard shortly thereafter, we see Rick Gilbert’s wife Anna astride a ride-on lawnmower cutting the grass. The two are maintaining the historic graveyard; it seems like they are the only ones who care. Gilbert takes a shovel and lifts away clumps of sod to reveal a flat cement grave cover with an indented cross that is filled with dirt. Gilbert scrapes the dirt away from the indentation; it seems obviously the grave of an unnamed child. No name is evident.

To punctuate the point, the film cuts away to archival footage from “The Eyes of Children” from 1962, an NFB production at the Kamloops Residential School, where Father Dunlop is bee hived by a collection of small female children, all of whom laughingly compete to be embraced by him in a friendly group hug, or to hold his hand as they all walk together across the schoolyard. A dozen other children run toward him, all seemingly very happy to welcome Father Dunlop into their midst. They appear to adore him, though the editorial context within “Sugarcane” implies a much darker meaning.

“93 is Our Number”

On Jan. 25, 2022, Chief Willie Sellars revealed the results of the Williams Lake community’s investigation in a press conference, presumably the one the film has partially documented, led by Charlene Belleau and Whitney Spearing. Excerpts of the press conference video in “Sugarcane” have Sellars stating that over decades of neglect and abuse, the dying and disappearances, “…something darker was going on.”

He states that the Ground Penetrating Radar (GPR) work has found 93 reflections, 50 of which are not within the cemetery, and all displayed characteristics of human burials.

This sounds gruesome. It should be recalled, as Robert Carney noted in his critique of the 1996 Royal Commission on Aboriginal People, that Indian Residential Schools, in the early days, were the hub of medical and social assistance to all who needed help. Recall that St. Joseph’s Mission was established there, 24 years before the school, in 1867.

Robert Carney was an eminent Canadian historian and a professor at the University of Alberta. He is the father of the much more famous Mark Carney who loves to brag that he was born in Fort Smith, NWT, but he is strangely silent when it comes to supporting his father’s legacy of work on Indian Residential School history. Mark Carney was named Britain’s most influential Catholic in 2015. Yet he has said nothing about the Catholic church burnings in his home country of Canada, nor has he defended his father’s research on Indian Residential Schools which clearly shows that thousands of orphans and destitute or endangered children were saved by Indian Residential Schools.

Robert Carney identified then, the problem with the current documentary “Sugarcane” and with the Truth and Reconciliation Commission as well as the work today of the National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation, that “the problem of ill-defined historical perspectives provides only a partial reason for the report’s imbalance.”

“The problem is that the Aboriginal perspective dominates virtually everything that is said. This is not surprising given that the linear perspective has been defined in such a way to exclude it from the analysis. As a result, Aboriginal residential schools are invariably cast in an unfavourable light. Whenever the schools are mentioned, they are found almost without exception to have failed to provide either acceptable care or education. The schools’ objectives, policies and practices are identified as a systematic strategy of cultural repression which was accompanied by an extraordinary amount of sexual, physical and emotional abuse. This is clearly a slanted account of these institutions, and therefore should be viewed cautiously because, to cite one of its problems, it tells only part of the story. The phenomenon of Aboriginal residential schooling is too complex and requires considerable nuance, as well as conceptual analysis, for simplistic historical interpretations to be serviceable. The Commissioners’ discussion of the schools fails to place them in a given historical and social setting.”

Carney continues:

“The work of the traditional boarding schools is similarly ignored in the chapter’s introductory section. The fact is that in addition to providing basic schooling and training related to local resource use, they served Native communities in other ways. It would have been fair to acknowledge that many traditional boarding schools, in some cases well into the twentieth century, took in sick, dying, abandoned, orphaned, physically and mentally handicapped children, from newborns to late adolescents, as well as adults who asked for refuge and other forms of assistance.”

Thus, it is quite possible that there are unmarked graves on or near the St. Joseph’s Mission graveyard which predated the school, that were burials of those who died, who had no relationship to the school other than that they came there for help and due to their condition, they died and were buried. In a time of many transient workers in the region, it is quite possible to acknowledge that there may be no record of the identity of a person, and thus one must not simply ascribe nefarious activity to their death or assume that a priest or nun purposely caused the death of someone.

Robert Carney also points out the social welfare function of schools, especially in later years, “But unlike most other boarding schools whose objective was to school children in a highly controlled residential setting, Aboriginal boarding schools were multipurpose institutions that took in many children who suffered from various forms of social, emotional and physical distress. The chapter contends that these “social welfare” functions did not become prevalent until a decade or two before the schools were closed. The fact is that Aboriginal residential schools always played a major role in caring for children in need.”

Children in Need

In “Sugarcane” there is a story told by Laird Archie, wherein he professes to have been friends with Ed Archie NoiseCat at school, because he, too, was rejected by his mother. He tells the tragic story that his mother, in a bar, gave him away as a six-month-old baby to an alcoholic couple who were there; that he endured a life of abuse with the adoptive mother beating him while he listened to the father raping his own eleven children every night. Laird’s thesis is that he and Ed bonded over that common rejection by their mothers.

Ed had mentioned to Julian on approach to Laird’s house that Laird had once kicked in Ed’s cheekbone in a beating enacted by Laird and two others.

Yet Ed and Laird share the name “Archie” — that of Ed’s mother’s maiden name. Are they cousins?

Ed says that he went to Indian Day School until grade 4 when he then transferred to public school.

In all, it is amazing that Ed Archie NoiseCat survived this on-going story of abandonment, public humiliation, rejection, and alcohol, which he confesses, ruled his life for much of the early days of Julian’s life. That he spent his days crying uncontrollably. That he had to leave. Abandon his baby son.

Imagine the gut-wrenching depths of pain that baby Julian must have stirred within Ed — seeing this tiny, vulnerable, wiggling thing — and realizing that once he, as such a tiny baby, had been dumped in an incinerator, left to die. By his own mother.

Out of those days of darkness, he found his way to sobriety and success, seemingly through his art. Only to venture today, back to the past with “Sugarcane” return to those dark days of his youth as the “Trashcan Baby” where everyone knew his humiliating story, as Laird revealed.

No wonder Ed moved to the US, far away from his past and his people. No wonder he never adopted the name of his father — Peters. Ray Peters. The man who fathered seven other children with Ed’s mother, and nine children with five other women.

No wonder, with all the diverse last names, the viewer of “Sugarcane” would never make these family connections.

No wonder film reviewers consistently agree that this is a story about genocide and the horrors of Indian Residential Schools, never questioning the family back story that makes it not one of institutional infanticide, but one of families drenching in alcohol and its related dysfunctions.

Intergenerational Trauma

It has another name in modern psychology, specific to this type of context. Adult children of alcoholics. This is an intergenerational phenomenon, as is that of ‘ambiguous losses’ — the sudden, tragic, unexpected death or disappearance of a loved one — or the unbridgeable distance to a loved one, physically present but psychologically/emotionally absent; physically absent but psychologically haunting you. There is no easy way to resolve this complicated grief. Indigenous psychologist Lloyd Hawkeye Robertson explains that there is a kind of Post Traumatic Stress Disorder that many former Indian Residential School students suffer from. But — it was not a genocide. He does not see books like “Grave Error” to be controversial in anyway.

But… ambiguous loss…

“The experience of ambiguous loss can bring unrelenting confusion and unending torment as the mind tries to make sense of the nonsensical. Paradox and contradictions abound. The goal of grief shifts from achieving closure to learning to live with grief by finding meaning.”

We see one such instance peripherally in the film when Stan, a good friend of Chief Willie Sellars, attempts suicide, is saved by paramedics, but not expected to survive.

The fear of loss.

The hope of salvation.

The depths of sorrow.

The digging of his grave.

Like an errant bullet in a hall of impenetrable mirrors, suicide also has intergenerational echoes; it goes on shattering. It’s a visceral wound that, for most loved ones, never heals. Integrating the loss is extremely difficult; the pain often drives loved ones to copycat suicides, either seeking relief from their sense of spiritual betrayal or hoping to reunite in the spirit world with someone they feel they cannot live without.

And suicides rates are epidemic in Indigenous communities.

And yet, we must choose life. Despite all.

19 This day I call the heavens and the earth as witnesses against you that I have set before you life and death, blessings and curses. Now choose life, so that you and your children may live and that you may love the Lord your God, listen to his voice, and hold fast to him. Deuteronomy 30:15–20

Though “Sugarcane” presents the case that all the on-reserve dysfunction is the outcome of Indian Residential Schools, the fact is that only one third of eligible students ever attended Indian Residential Schools and in the pre-World War II period, most student graduates found careers and work; many became the Indigenous leaders who created economic opportunities for their reserves — people like Rick Gilbert.

It is in the post-World War II period, when alcohol became widely available to Indigenous people that crisis dysfunctional problems arose (prior to the war alcohol had been tightly restricted). This is when family dysfunction and Fetal Alcohol Syndrome rates skyrocketed. This is when villages like Alkali Lake — often known as “Alcohol Lake” popped up all over. This is when Indian Residential Schools began taking in FASD children, some of whom had serious behavioral problems that ended up being foisted upon other hapless children who had come there for an education, or upon the lonely orphans who had been placed there because their parents or guardians had died. Like the paternal grandmother caregiver of Ed Archie NoiseCat who died of alcohol poisoning, drunk and falling in the snow where she froze to death.

In “Sugarcane” Ed finally does go home.

And here is the final exploitation of this family’s deeply wounding tale.

As the camera focusses on the outside of his mother’s house, Ed, the abandoned son, and Julian, the estranged son, enter. We hear voice over that Ed says to his mom (who we had seen earlier in the film, but who remains unidentified by name), “We are on a journey, trying to heal…” He explains that there’s a gap in his existence as a baby and he wants to know what happened, to find some peace.

That’s all valid. I suggest it does not belong in a film for worldwide distribution.

His mother’s anguished sobbing voice tells us all we need to know. None of this should be on film. It should be in the office of a priest, a psychologist or counsellor. The raw pain is evident in her voice “I don’t like to talk about it…I went through a lot with this. It sticks with me all the time. I pray all the time…”

The fact that his mother is not on camera and not identified by name on camera suggests that this was an ambush documentary — a shock-u-mentary — that completely ignored fundamental principles of informed and ethical consent.

And which completely distorted the facts of the family story, making us believe this is evidence of genocide by Catholic priests and nuns when the evidence does not support the claim.

What of the fact that during Rick Gilbert’s visit to the Vatican, he ‘confides’ (on film) to Louis Lougen, Superior General of the Oblates of Mary Immaculate that he is there because his mother was abused by a priest while at Indian Residential School, and thus he exists.

Again, unless Rick knew something he did not reveal to the filmmakers, in a province dotted with McGraths, and a gold rush town filled with Anglo-Saxons of 31% English, 18% Irish and 24% Scottish ethnic roots, many men could have fathered Rick Gilbert.

“Sugarcane” is deeply deceptive, and therefore cannot be properly called a documentary. Just read the myriad of enthusiastic reviews — most of which claim there was a genocide or infanticide in Canada at Indian Residential Schools.

Never proven. No evidence.

National Geographic is engaged in promoting a tale that slanders the many innocent and dedicated Catholic priests and nuns at Indian Residential Schools, many of whom spent their lives there, assisting the children in their care.

Hundreds of these priests, nuns and staff were themselves Indigenous. They faithfully served these Indigenous children, many of whom were abandoned or orphaned; thousands of children were given genuine love and care, education and sustenance by those who took them in, albeit there were abusers among those charged with their care, but few over the 113 years of operation of all Indian Residential Schools and the 90 years of operation of St. Joseph’s.

Since there were so many Indigenous servants of Christ and staffers at Indian Residential Schools, it is inconceivable that they witnessed ‘genocide’ or infanticide of their own relatives and said nothing.

By a continual focus on Indian Residential Schools as the sole problem facing Indigenous people, with the amplification of lurid whispered tales of children as if fact, but with no evidence, and with the focus of ‘funding’ as the alleged solution, these intergenerational traumas will go unaddressed and will continue to decimate youth.

Every child does not matter if you don’t care about what I have just revealed.

That is the fact check.

Will this back story awaken audiences and transcend their moment, National Geographic?

Will anyone care? Facts matter, no?

Footnote — Just as I’m about to post this…

The final cruelty, in my opinion, as a filmmaker and writer myself, is that the film “Sugarcane” will be featured at TIFF, the Toronto Film Festival, on Baby Ed Archie NoiseCat’s birthday. This seems unduly exploitative, to me.

Happy Birthday, Ed. I do sincerely hope that you and your family found closure.

Ed, you are a wonderful artist and a testament to the human spirit that you surmounted the cruelty (perhaps unintentional) that you faced from the beginning of your life. Your son, Julian, is obviously a talented young man.

However, I can’t countenance how your tragic family story has been used to vilify others in this documentary, many of whom are dead and cannot defend themselves, and thus, this worldview continues a cycle of victimhood.

That’s something that you have left behind.

Hopefully that part of your story will provide a role model to young people. Hopefully other young people will, as you have done, take the challenges of life into their own hands and shape a beautiful future rather than descending into despair.

30-

Related:

Ambiguous Losses: Epidemics, Orphans, and Unmarked Graves

Mass Grave Mass Psychosis: Responding to Gerbrandt and Carleton’s “Debunking the Mass Grave Hoax”

Michelle Stirling is a former member of the Canadian Association of Journalists. She researched, wrote, and co-produced historical shows about Southern Alberta under the supervision of Dr. Hugh Dempsey, then curator of the Glenbow Museum. She also researched and co-wrote a documentary on genocide; the factual content so dark the producer decided not to release it.

I wrote to National Geographic about their descent into the cult of fabrication for money.. They have an online contact form here https://support.nationalgeographic.org/s/contactsupport

I imagine that if enough Canadians push back directly to them, the house of cards might start to crumble.

Thank you so much for this work. It is highly unpopular to question or investigate critically anything that has to do with Indigenous people. It is such a loss for our country, we had an opportunity to find true and good ways to "walk together" and there is SUCH a willingness in most Canadians to learn and engage with Indigenous communities, but they turned to the grift and ran with it dishonestly. I find that hard to forgive, even though I do understand how alluring victim mentality combined with financial reward and social status can be for all humans.