The Trail of Tuberculosis Through the Percy Nabigon Story

TB is the Culprit, Not Indian Residential Schools

By Michelle Stirling © 2025 With files from Nina Green and Pim Wiebel

“In no instance was a child awaiting admission to [Indian residential] school found free from tuberculosis; hence it was plain that infection was got in the home primarily.”

- Dr. Peter Bryce

“Everything is Tuberculosis” is the title of John Green’s latest book. A self-reported sufferer of Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD), Green’s book presents the thesis that Tuberculosis – or TB – as it is commonly known for those who remember it, radically affected all of society, even today, in ways we do not understand.

I agree with him. For those who are not so keen on reading, I strongly recommend watching the PBS documentary “The Forgotten Plague” which is what TB is today.

https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/films/plague/

As my readers know, I am a proponent of academic and research freedom on the topic of Indian Residential Schools and allegations of “missing children” and “unmarked graves.”

I was part of a Greg Wycliffe round table discussion on X with Frances Widdowson and Jim McMurtry and others on the upcoming 4th anniversary of the Kamloops First Nation’s claim of finding a mass grave of 215 children and human remains. As part of the show, I had spoken of my articles, and Nina Green’s research, about Percy Nabigon.

The Onabigon family claim is that Percy – their mother’s sibling and a child who was reportedly ‘forced’ to go to Indian Residential School - was partially paralyzed and epileptic. Though various medical issues can cause these conditions, Tuberculosis is a likely culprit, both for seizures and paralysis if the spine is affected. In the 1930s and 40s, streptomycin and BCG vaccines (which are only effective in certain circumstances) were in development, but still far from market distribution. As per the Percy death certificate, “marasmus” – extreme malnutrition – was a contributing factor to his death.

The Nabigon family is insistent that Percy went to Indian Residential School, despite the existence of a death certificate for him as a baby. But that’s not the point of this article.

The key point is that the Nabigon family story, is being used by Kimberly Murray in her reports and advocacy, as an example of a child who was forcibly and nefariously “disappeared” by the Indian Residential School system, the Catholic Church and the Canadian government. But this contention is both an anachronism and is not supported by documented evidence of the time.

For Canadian taxpayers, it is important to understand that the Indigenous reparation activists not only want more apologies, but they want more financial reparations for these alleged “human rights crimes” (such laws did not exist at the time), and they want you to pay to repatriate the bodies of any Indigenous person who was cared for but died as a child or adult, in any such facility, be it a TB Sanatorium, mental institute (known as asylums back in the day), home for the disabled, Indian hospital, reformatory, or home for unwed mothers.

Note, some researchers have equated Indian hospitals as evidence of racial discrimination, when, at the time, Indian hospitals provided preferential treatment for Indians who received free care, paid for by the government, while non-Indigenous Canadians had to pay for all their medical care. “Free” Universal Health Care was not instituted in Canada until well into the 1970s and was only formalized federally in 1984 with the Canada Health Act.

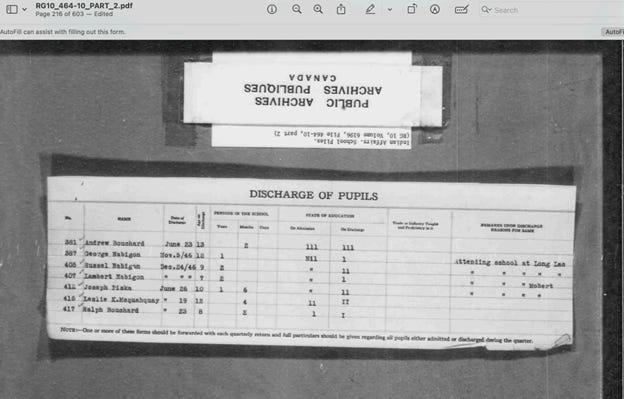

Had “Percy” been registered at the Indian Residential School, his name should have appeared on this discharge form as well as the names of the other Nabigon children.

Nina Green writes: Earlier, the family had maintained that Percy was at St Joseph's for 2 years, and in her final report, Site of Truth, Sites of Conscience, in October 2024, Kimberly Murray said the same, but it appears the family recently changed that story to 2 months). Here's Kimberly Murray's account from Sites of Truth in October 2024:

Although Percy Onabigon was well cared for by his parents, in September 1944, when he was just six years old, he was taken from his home community of Long Lake #58 First Nation to the St. Joseph's Indian Residential School in Fort William, Ontario (now known as Thunder Bay). Percy had epilepsy and was paralyzed on one side of his body. In 1946, a doctor reported to the Indian Agent that "hospitalization at Toronto would be the answer. It was recommended that Percy be transferred to the Hospital for Sick Children in Toronto. Following this recommendation, on November 6, 1946, Percy was discharged from the St. Joseph's Indian Residential School and first sent to the McKellar Hospital in Fort William.

Nina Green notes: If Percy had been enrolled at St Joseph's he would be on the same December 1946 discharge form as George, but he's not. George was discharged 5 November 1946 (see screenshot above). Kimberly Murray says Percy was 'discharged' on a doctor's recommendation the next day, 6 November 1946.

Clearly, Kimberly Murray’s claim that “Percy was well-cared for by his parents” is in doubt as the medical record for Percy, who died in 1938, indicated that the secondary cause of death, after TB, was marasmus - severe malnutrition.

Recall that in the late 1930’s, Canada was in the depths of the Great Depression when millions of Canadians of all ethnicities were jobless, homeless, many on the brink of starvation or suffering from malnutrition.

Source: https://edmontonjournal.com/news/local-news/oct-1-1932-no-more-free-rides-for-hoboes

In a recent edition of “The Road Home” (May 11, 2025) on CKUA Radio, Bob Chelmick played an interview clip with prairie poet and author Lorna Crozier who told the story of her mother, who came from a family of 7 siblings. Lorna recounted that at age 4, during the Great Depression, her mother was given to the neighbours as a live-in household servant. She stayed there until she was 7 years old, missing her first year of school. When a shocked Lorna asked her mother about this, her mother flatly replied, “If you had 8 children then, you’d give one away, too.”

Indeed, Brian Giesbrecht, former provincial court judge in Manitoba and author of numerous articles on Indian Residential Schools, has noted in correspondence that the federal government provided additional funding to Indian Residential Schools during the Great Depression so that more children from destitute families could be supported.

So, the true irony of the condemnation of the Indian Residential School system and government care of children by the Indigenous activist “body-repatriation-and-reparations” movement, whether in the school or in other medical institutions, is that many families needed such 24/7 ‘day care’ due to poverty and too many mouths to feed. Further, up until about 1950, Canada’s leading cause of death, for all people, was Tuberculosis.

Source: https://www.abebooks.com/9780802022691/miracle-empty-beds-history-tuberculosis-0802022693/plp

The Nabigon family story is an exemplar of that. The records show that not only was Percy partially paralyzed and epileptic, but that his father was ultimately sent to a TB Sanatorium, at which time the children were taken in by St. Joseph’s Indian Residential School. Also, brother George was treated for TB for a short period of time as well.

In the Department of Indian Affairs school records, Nina Green has recovered enrollment forms for the more healthy, active children, but there is no record for “Percy.” Based on the family’s description of his partial paralysis and epilepsy, he would not have passed the medical exam to be admitted as an IRS student, but the school may have taken him in out of mercy for transitional care until other long-term arrangements were made. The school would not have received government funding for such charitable care, and therefore no records would have been required.

The Nabigon family’s complaint is that “Percy” was forcibly taken away to the school – for which there are no such records - and they claim that he was subsequently taken away from the school without consent of the family and thus was “disappeared” as if with nefarious intention. As I’ve mentioned in other articles on Substack and Medium, it was common up to the 1970’s for families to give over disabled or difficult family members to the government as Wards of the State, after which, the government decided the person’s care, generally without consultation with the family.

In fact, the Canadian government gave Percy Nabigon ~20 years of institutional care, at no cost to the family, for a child, then adult, who suffered from severe medical issues, likely related to Tuberculosis. And, as per Moffat, the Nabigons had a brother, they only knew as a child; one who sadly did not return home from extended care. Josh Green writes that TB Sanatorium care numbers suggested that perhaps only ¼ of patients would survive.

This loss of family connection was not an uncommon experience for Indigenous and non-Indigenous families alike. In Josh Green’s “Everything is Tuberculosis” he tells the story of a little non-Indigenous girl named Gale of Boston, who entered a TB Sanatorium in Massachusetts at age 3 and left at age 16. (pg 104) This parallels a story of an aboriginal family told in Moffat et al (2013), summarized in my Medium post on “Unmarked or Mass Graves? Epidemic or Genocide? Some Historical Context on Canada’s Residential Schools.”

Due to the long treatment periods, contact with family, culture and heritage was lost. One aboriginal testimonial in Moffat reads: “My brother went to the sanitorium and stayed there for seven years because he was allergic to the medication. It took seven years for the tuberculosis to go dormant. I never knew my brother. My older sister has no memory of him. My siblings never met their brother until he was thirteen. He was a total stranger. That’s the emotional part — that we had a brother we never knew.” Moffat et al (2013)

An issue I will not address in detail in this article, is that of the social stigma attached to Tuberculosis, which was often the “kiss of social death” to individuals or family. For centuries, it was thought that Tuberculosis was hereditary. Then came the discovery by Robert Koch of the Tuberculosis bacillus. The invisible but deadly germ. TB is contagious!

As Josh Green also writes, once it was determined that an invisible germ could attack and kill you from the inside out, the feelings toward the infected sufferers of TB was one of fear and revulsion. It was common to cut ties with family members suffering from TB, sometimes in order to survive socially in your own community. Historical references I have found elsewhere note that family members who died of TB were often buried in an unmarked grave to prevent ostracization of the living relatives from society. Such social exclusion is the case today in Northern Indigenous Communities where the social stigma of a TB diagnosis contributes to lack of care for infected persons.

So, consider the selfless charity of the priests, nuns, other clergy and staff who willingly served children whose families were in care or who had died of TB, knowing that they, too, risked infection. Consider why cleanliness and harsh discipline about the sharing of personal items or food was so strict at these schools – those in charge were trying to ensure any potential infection could not spread.

Josh Green quotes Conan Doyle of Sherlock Holmes fame, who wrote of TB – “What an infernal microbe it is! …How absurd that we who can kill the tiger, should be defied by this venomous little atom!”

Another argument, sure to surface in the Nabigon case, is that Tuberculosis was contracted at the Indian Residential School. As noted in the first quote above by Dr. Bryce, it seems likely to have originated in the home.

The book I mentioned in the beginning of this article, “Everything is Tuberculosis” by John Green, sadly gives a false report about the TB statistics at Indian Residential Schools.

Pim Wiebel (pseudonym) is a researcher and writer on this topic. He explains:

There has been a perplexing confluence of federal agencies, academic institutions and mainstream media reporting a preposterously exaggerated statistic on tuberculosis mortality in the residential schools. Theresa Tam, Canada’s chief public health officer, stated in a report published in 2018 that, “In the 1930s and 1940s TB mortality rates exceeded 8,000 per 100,000 among children confined to residential schools…” Tam compared this rate with the rate of 700 per 100,000 among First Nations living on reserves, which is the correct annual death rate figure for the two decades.

The same statistic had previously been reported in a Globe and Mail opinion piece. University of Alberta Department of Medicine researcher Courtney Heffernan repeated it in a 2022 article in the International Journal of Tuberculosis and Lung Disease.

The 8,000 per 100,000 statistic for the residential schools is absurdly overstated. Graph 5 in the TRCs Summary of the Final Report indicates annual tuberculosis death rates in the residential schools up until 1965. The average annual residential school death rate from tuberculosis in the 1930s and 1940s was approximately 200 per 100,000, about one-fortieth of the 8,000 per 100,000 claimed by Theresa Tam.

As late as 1943, the annual tuberculosis death rate in the reserves was still nearly 700 per 100,000. The rate in the reserves in the 1930s and 1940s was thus more than three times higher than the 200 per 100,000 rate in the residential schools during the same period.

Canadians have thus perversely been served a grossly inaccurate statistic on residential school tuberculosis death rates by Canada’s top health official, by its “most authoritative” newspaper, and by a leading researcher in tuberculosis epidemiology. An unknowing Canadian public has little alternative to simply accepting the official distortions as fact.

What is clear in the Nabigon family story, is that TB and malnutrition likely caused the death of Percy as a baby in 1938. Whoever the 8-year child is who the family claims is Percy, lived with physical paralysis and seizures, likely due to spinal TB infection. It is clear that the family was destitute, as the death certificate records the causal factor of death of Percy from marasmus. Historical records show that ultimately the father, Duncan, and brother George, were also treated for TB, and that Percy who wound up as a Ward of the State, subsequently died of TB at age 27 and was buried near Woodstock.

Throughout numerous stories of Indian Residential School ‘survivors,’ the thread of Tuberculosis is ever present, resulting in whole families wiped out – like Stephen Kakfwi’s mother, whose entire family had died of TB. Kakfwi is the husband of Marie Wilson, former Truth and Reconciliation Commissioner (TRC). Despite her intimate relation with Stephen, somehow the impact of TB on the lives of students barely features in the TRC reports.

Like her deceased family, Stephen Kakfwi’s mother was also infected with TB, and that resulted in her spending six non-consecutive years of the first twelve years of Stephen Kakfwi’s life in a TB sanatorium, far from home. Think of the disruption to the maternal-child bond… but she did survive and was an amazing role model for her son.

The historical context shows us that TB killed one or both parents, leaving children orphaned. TB disabled many surviving children leaving them encumbered with physical disabilities, like those suffered by Rose Prince. The long separations of loved ones, the years of recovery led people to believe children had ‘disappeared’ from Indian Residential Schools, when they had been sent on for care at TB Sanatoriums. The historically appropriate, but cruel and painful forms of treatment for TB (such as lung collapse) were undoubtedly experienced by TB sufferers as intentional torture, especially children. In my opinion, these experiences with painful TB treatments are likely conflated with Indian Residential Schools ‘memories’ of torture at these schools, and in my opinion, are most likely the source of many of the more lurid claims of ‘torture’ by some former students.

Just watch the beautiful and heart-rending Canadian film “The Necessities of Life /Ce qu'il faut pour vivre” and you will see what a shock it was for a native person from a remote community, living off the land, to be treated for TB in an urban sanatorium. This was a place that the Canadian government sent him to be cured - saved, not destroyed. But was he demoralized by it all? Yes.

Likewise, you will wonder, if the Canadian government was intending to ‘genocide’ Indigenous people, why did it bother to try and treat Indigenous Tuberculosis sufferers at all?

After all, it was well recognized that Tuberculosis was the greatest killer of all humankind, and was the “Captain of all these men of death.”

The trail of tuberculosis runs right through the Percy Nabigon story. So, were Indian Residential Schools responsible for all of today’s aboriginal problems…or shall we consider Occam’s Razor - the simplest explanation. TB. Captain of all these men of death. Then. And now.

30 -

Additional Resources:

Fatal TB Meningitis in UK Infant

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8378383/

Valerie’s story of TB Menigitis

Why does TB have such a hold on the Inuit communities of the Canadian Arctic?

https://www.npr.org/sections/goatsandsoda/2024/05/02/1247521186/tb-tuberculosis-inuit-canada-arctic

Life was very hard for people, like Percy and his family. Now, like flies on their sad corpses, many feed off their misery

Those who happened to watch the video in the most recent CBC piece about Percy might recall that one of the guests at the exhumation was a Six Nations chief, Claire Sault, who is filmed in the video saying, “Imagine how many more Percys there are.” https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/thunder-bay/percy-onabigon-remains-repatriated-residental-school-1.7525722

The Onabigons gifted Sault a beaded medallion “for KEEPING PERCY’S REMAINS SAFE in her traditional territory for so many years.”

I commented to a friend that gee, it must have been a TON OF WORK for Chief Sault to keep that grave “safe” all those years! She’s only been chief (of the Mississaugas of the Credit River) since December 2023, and “her traditional territory” is also the traditional territory of a dozen other Mohawk “Nations” – and millions of Canadians.

So I ask: Where’s the Province of Ontario’s medallion for keeping Percy ALIVE for 20 years, marking and maintaining his grave for 59 years, and now paying for his exhumation?

No gratitude or acknowledgement there, just excoriation for “hid[ing] him until he died,” as Claire scolds.